Reform's biggest problem: People agree with them

British politics is a world without self-interest.

“You all laughed at me,” said Nigel Farage as he trembled, giddy with euphoria. “Well, I have to say, you’re not laughing now, are you?” He delivered this last cheer as he gazed upon a sour Jean-Claude Juncker. Brexit had been won; the damp grey bank clerks had been defeated, and now was the time to celebrate or maybe even gloat. Farage now seems to be on the precipice of the greatest “I told you so” of all, becoming Prime Minister, but this very fact could be what keeps him out of Number 10. The Reform leader’s biggest challenge isn’t any policy but something far more difficult: not looking smug. In 21st-century Britain, vision can’t get you into power, but resentment can keep you out.

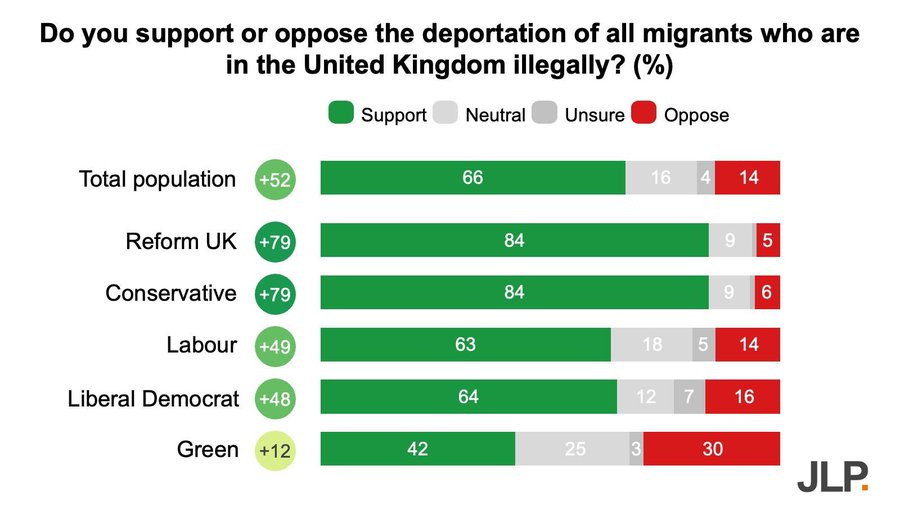

People will vote for Reform UK to decrease and reverse immigration. Every other political action from the party is done in part to show they could carry out their main goal. This will be part of a generalised attempt to return Britain and its people to how they looked in the early 2000s. Only Fools and Horses, the old Top Gear, or Love Actually – take your pick – but the goal is a country which is more homogeneous in every facet that entails. Despite the shocked reactions from centrist and left-wing politicians, Reform’s policies to make Britain both feel and look more like the 2000s are very popular. A JL Partners poll found huge majorities for the deportation of all illegal migrants, with 66% of voters agreeing with Reform’s flagship policy and only 14% against. Nigel Farage is, despite his success, a long way from two-thirds of the vote. The key to British politics is the voters who agree with Reform but won’t vote for them.

In their defence, it is not their fault immigration is a problem again. They voted against Brexit and mostly against Johnson, the “Boriswave” is certainly not on their hands. They lament, like Alastair Campbell, that young Italian waiters have been replaced by Indians with countless dependants. All their warnings about Boris the Buffoon, Tory incompetence, and of course Brexit seem to have come true, but have woken them up in the midst of another nightmare. Some will call them elitist or insulated from the damage done by recent migration, but why should they have to swallow the bitter pill of voting for Farage? All the while, the salmon-trousered Reform leader takes advantage of the next crisis to fall into his lap. The historian Louis Namier famously ascribed the politics of 18th-century England to pragmatic self-interest. Local merchants solely wanted more trade in their port, landowners’ positions for their sons, and so on. Now we live in a land of pragmatic selfishness in which material interest is forgone purely to deprive one’s former opponent of a victory he certainly doesn’t deserve.

Is there anything Farage can do to prevent a wave of spite-fuelled tactical voting? I suspect not. Although understudied, the UK already has a very recent exemplar of large-scale tactical voting over the last decade: Scotland. I grew up in a land where every election was a referendum. Conservative votes in places like Perthshire were held up by massive unionist tactical voting, but even this was only really successful in 2017. The closer the SNP got to independence, the more willing people were to compromise and vote along purely constitutional lines. Some soft SNP voters who didn’t want Independence abstained or changed their votes. (There are always those who like to dance on the edge.) The same will apply to Reform. Bizarrely, the larger poll lead they have, the more likely those that dislike them are to vote solely in order to block them. We already live in a world where most vote against their material self-interest; Labour’s strongest supporters are the upper middle classes most punished by their policies.

These same people, who have learned nothing and forgotten nothing from the shattering of their world following the financial crash, still have the political force to stop their enemy’s circus coming to power. In British politics, we are all arguing about who should have the last laugh.