The Forgotten Explorers

The British discovery of the Pyrenees.

It is hard not to think of the Victorian world without its explorers. From Darwin’s Beagle, “Dr Livingstone, I presume,” and the terror of the Northwest Passage, the search for the new limits of the ever-shrinking world knew no bounds. However, this impulse was not confined to the Arctic wastes and African interior. Far closer to home, the peaks of Europe provided another challenge to the restless 19th-century mind. The towering Alps, dividing the great French and Italian civilisations, presented the first challenge, but to the west, a few men began to discover a range far more removed from the world’s imagination: the Pyrenees.

Now, as with all good stories, nothing is quite as undiscovered as it first appears. The French hadn’t been totally lacking in ambition or curiosity when it came to their own mountains. Indeed, by the time the first British gentleman explorers arrived, most of the great French peaks had been climbed and mapped. The same, however, could not be said of the Spanish side of the massif.

This is more due to the physical character of the Pyrenees than the laziness of the Spanish, Basques, Catalans, and Aragonese who dwell on that side of the border. On the northern French slopes, the mountains are penetrated by long valleys which quickly break from the rugged alpine terrain into broad valleys. This led to many settlements, most famously Bagnères-de-Luchon, Luz-Saint-Sauveur, and Eaux-Bonnes, which sit almost at the foot of the great peaks.

On the Spanish side, the foothills are far more stubborn, with steep, tree-lined defiles and canyons continuing for mile after difficult mile. As such, civilisation has always been further away from these southern slopes, as even today an unfortunate traveller caught on the Spanish side in search of a way home can testify.

This situation was ideal for the Britons who, bored of the Alps, wanted to explore virgin territory. One of these was Charles Packe, a lawyer who, after a first trip in 1853, would devote his life to exploring the Pyrenees. Initially, he followed the tracks of smugglers and shepherds. The snow- and ice-bound high passes were ideal for those seeking to avoid the wrath of customs officials. The central Pyrenees contain relatively few passes and those which there are like the infamous Portillon de Benasque were wild places , or as locals said “Where father does not wait for son and son does not wait for father.”

Packe’s main exercises in exploration were long week or even month-long chevauchees into the depths of the mountains, which, progressing in a circle, brought him back to where he had set off after many days.

While he initially concentrated on the areas which were somewhat known, he soon focused his attention on the Balaitous. This, one of the giants of the Pyrenees, is unrivalled in stature by its neighbours and is isolated from any of the towns in the French region. Having tried the year before unsuccessfully, Packe sought the following year to make a successful summit for the first time (unbeknownst to him, the mountain had been climbed in 1820 by some French engineers stationed below).

The ascent began on smugglers’ paths up from Arrens-Marsous. Eventually, Packe and his guide branched off from this main valley and up a steeper one which brought them to the western shoulder of the mountain.

The main valley went on, as it still does, to the Col de Peyre-Saint-Martin, one of the most popular smuggling routes in the range, and where shepherds from either side of the border would meet every year to settle disputes about cattle lifting. Be they shepherd or smuggler, all who passed over the col left a stone at the top, creating a great cairn which is still there to be admired to this day.

Packe continued with his shepherd guide up towards the realm of ice which guarded the highest slopes of the Balaitous. The gentleman explorer was somewhat of a revolutionary, with a sheepskin sleeping bag he had made himself and a pack weight of only 3.5 kg, putting many ultra-lightweight devotees today to shame.

Walkers then, as they can today, could receive sustenance from the shepherds’ cabanes and, in Packe’s case, from those of the fishermen catching mountain trout.

This, however, was the easy part. While now we may be used to a waymarked route, or even if there is no route, a bearing or GPS track to follow, in Packe’s day there was no one alive, at least to his knowledge, who had completed the ascent. He would spend six days trying to find a way up the higher slopes.

Eventually, Packe would find a way through this maze of ice and rock, reaching the summit as ever with his faithful dog, named Ossoue. Packe completed every summit he did, including the first ascent of the Pic Carlit and the first mapping of the Monts Maudits, with his Pyrenean mountain dog, and would go on to be the first to introduce the species to Britain.

The only equipment for this and his other ascents was an alpenstock (a shepherd’s crook with a very rudimentary spike for the ice) and occasionally a piece of rock which acted as an ice pick. Partly, the ability of these tourists to climb such mountains was due to the huge extent of permanent snow and ice. This made most of these walks not easy, certainly, but completely different from the landscape the hiker sees today. Spires of rock and scree would have been covered by snow and small glaciers, completely changing the nature of the mountain.

Packe was not alone as a native of the British Isles in love with the Pyrenees. His friend Henry Russell had many more first ascents than even Packe. Russell an Irish nobleman and devout Catholic was so beloved that Pic Russell in the Maladeta massif still bears his name. However, Russell will forever be associated with the Vignemale.

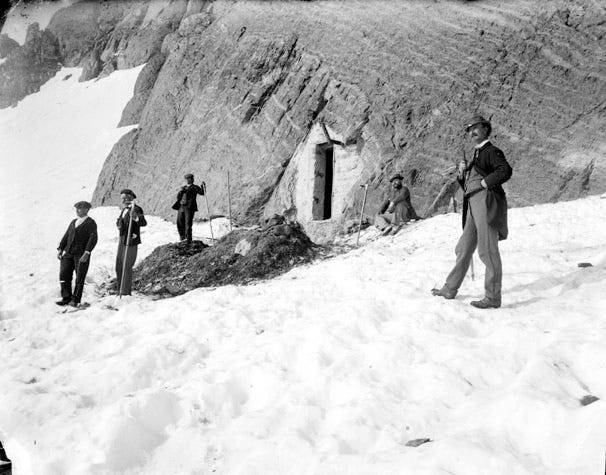

The Vignemale is France’s highest mountain in the Pyrenees and home to the Ossoue glacier, which one has to cross in order to reach the summit. Desiring to spend more time on the Mountain, Russell had a series of caves dug into the rock near the summit.

These, which can still be seen to this day, allowed him to spend day after day on the mountain’s summit. Russell would go on to dig more caves at the foot of the glacier known as the Bellevue caves. These are passed by thousands of walkers each year on the GR10. However, the damp shelter they offer now was once held almost oriental splendour. Russell would host visiting noble and celebrities in his hollows with the floors bedecked in Persian rugs and put on banquets “like those of Lucullus”. He even bought the mountain off the French Government for this purpose. The Irish count would climb the mountain 33 times and on of his last ascent in 1904 would spend 17 days on the summit.

Russell is commemorated not only with a peak he made the first ascent of, but also a statue in Gavarnie beneath his beloved Vignemale. Packe is not as celebrated, although remarkably Packe’s guidebook would be the only English guide to the Pyrenees until 1978, 117 years after his work was first published. Walking through the Pyrenees now, there are few people from the British isles. Hopefully this article inspires more of you to follow the path of those 19th century pioneers.

If you want to follow Packe’s 170 year old guide the link is here https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Guide_to_the_Pyrenees/SHhIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

If you want to read more about the Pyrenees please see my stack on my journey through the Basque country:

Force Basque! Tales from the Haute Route Pyrenées Part 1

The Pyrenees are Western Europe’s forgotten mountain range. Overshadowed by the greatness of the Alps, their difficulty of access and less popular pistes make them the poorer relation of France’s two great massifs. However, over the last three years, I have been lucky enough to walk the spine of this chain of mountains which separates France from Spain.…